Originally run on 30 November 2009 in the Union Weekly.The Proposition (2005)"Australia, what fresh hell is this?"

Originally run on 30 November 2009 in the Union Weekly.The Proposition (2005)"Australia, what fresh hell is this?"It’s probably telling that

The Proposition is one of my favorite films, since it’s one of the most stark and depressing films that’s come out in the past decade. It’s also the single best western to come out since

Unforgiven, which is strange considering the film was written and directed by Australians and takes place on the same continent. It is an unusual place for a setting, but like Sergio Leone’s comic book melodramas or Akira Kurosawa’s samurai-filled iterations, taking the western down under breathes life into the genre. It’s an odd choice, but it’s the kind of choice that keeps the western alive.

The director of the film is John Hillcoat, an Australian who recently released the film adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s

The Road. He’s clearly a man who knows how to put together a good movie, but what elevates

The Proposition above most other films is the screenplay written by musician-cum-novelist-cum-former-heroin-addict Nick Cave, who also handles the score with bandmate Warren Ellis (not to be confused with the comic writer of the same name). Cave, though an Australian exile living in England, has an excellent handle on the western and American writing, an influence that’s quite clear in both his lyrics and in his debut Southern gothic novel,

And The Ass Saw an Angel.

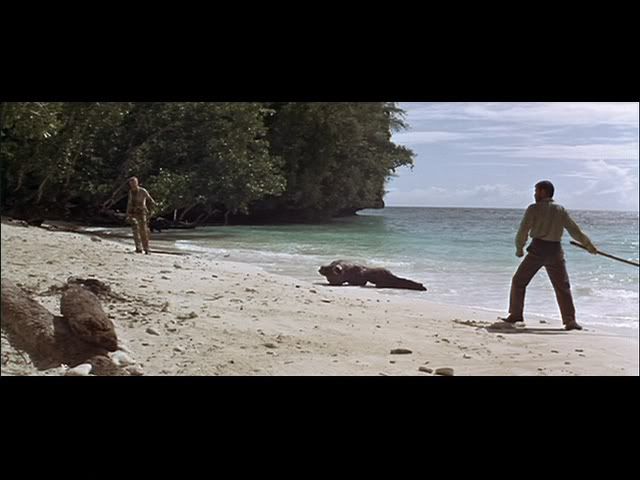

The film takes place in the year 1880, back before Australian independence, racial tolerance, and dental hygiene. The Australia of

The Proposition isn’t the place we laughed at in that one episode of The Simpsons. Instead of koalas and lame jokes about knives, this Australia is one that’s basically unknown to us and, as I understand it, unknown to even the Aussies. This land is a fly-filled hellhole rife with delusional government officials, psychopaths, wars with the natives, and miles and miles of dirt. If the entirety of the United Kingdom was shaken up, all of the loose pieces of trash and deritus would wind up in Hillcoat and Cave’s vision the Land Down Under. It’s in this topsy-turvy terminal that our protagonist, Irish immigrant Charlie Burns (Guy Pearce) finds himself caught up.

The opening of the film is rather telling. It begins with the police ambushing Charlie and his youngest brother, Mike, at a brothel in the middle of the desert stocked solely with Chinese prostitutes. It’s a loud, brutal fight and ends with the two Burns brothers captured by police. But they aren’t executed or sent to prison. Instead, police Captain Morris Stanley (Ray Winstone) offers them a proposition: If Charlie Burns kills his eldest brother, Arthur who is “an abomination,” by Christmas Day, Stanley will let Charlie and his younger brother go free, absolved of all of their crimes. If not, Mike will be put to death for the crimes of the two older brothers. From there, the movie unspools into an anarchic, bloody race against time across the sun scorched wilderness of Australia.

The eponymous proposition is about as Biblical (or maybe Faustian) of a pact as could ever be made, but unlike the Bible, there’s no moral to be found, there’s no lesson to be learned, and nothing seems to occur according to any divine purpose. Things just happen and they’re incredibly ugly when they do. The world of The Proposition is deeply flawed and demonstrates just how messy things can be when humans try to do the right thing. It’s an interesting inversion on the typical representation of the western as the forces of good battle the forces of evil, and it’s what makes this movie more than just a simple piece of genre.

The film is also chock-full of wonderful acting, including a performance by one of my favorite character actors of all time: John Hurt. Hurt plays Jellon Lamb, a verbose and sadistic bounty hunter, adventurer, and “man of no little education.” Hurt’s career has spanned about 50 years and he’s acted in projects ranging from fantastic fare like

Hellboy and

Alien to more serious dramas such as

Midnight Express and

The Elephant Man, as well as the other great western of the past two decades,

Dead Man. With all of these films in mind, I’d be hard-pressed to find a movie where he’s more engaging than here. He’s creepy, threatening, and hilarious all wrapped into one man.

Now, while he is my favorite actor in the film, he’s really a part of a much larger ensemble of great actors. There’s the beautiful Emily Watson (

Punch Drunk Love; Synecdoche, New York), as the delicate, but frustrated wife of Captain Stanley, as well as David Wenham (

Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, 300) as the wonderfully named Eden Fletcher, the dandiest authoritarian that ever drifted into the Victorian Outback. Danny Huston (son of the great actor/director John Huston) is also great as the villainous older brother, Arthur, who is as vicious and frightening as he is charming, a difficult combination to pull off and is entirely appropriate for this film.

It’s a shame to know that

The Proposition’s unrelenting grimness will keep a lot of people from seeing it and just as many from finishing it. Their loss, I suppose, because despite the film’s bleak treatment of humanity (and of Australia), there’s still a beauty to be found in all this. Hillcoat’s film shows that as wicked as we might become, there’s still redemption to be had, if only we can find it. There’s plenty more to be sussed out of the film, but if there’s anything more significant, I’d be hard-pressed to find it.